Traducción

Argentina durante la II Guerra y tiempo después

Para los que sobrevivieron y se encontraron vivos, el final de la guerra no fue un momento de celebración o alegría.

Europa estaba cubierta por la sangre de las familias desaparecidas y también debían enfrentar la amenaza de la Guerra Fría. Sabían que debían encontrar otro lugar donde vivir.

Sin embargo, el triste resultado de la conferencia de Wannsee de 1938 -que ningún país aceptaba recibir a los refugiados alemanes y austríacos- se repitió al final de la guerra. Los sobrevivientes no sabían dónde podían ir.

Mis padres, que habían sobrevivido e la guerra en Polonia y que habían perdido a su primer hijo, ya me tenían a mi y, junto a tantos otros, buscaban un país que nos recibiera. Las embajadas y consulados tenían largas filas pero sin buenas noticias. Y no les llevó mucho darse cuenta que el problema era que eran judíos.

Decidieron decir entonces que eran católicos, dado que ya tenían experiencia en hacer lo que fuera para sobrevivir. Así fue como, soborno mediante, obtuvimos visas para ir a Paraguay.

¿Paraguay? ¡Qué palabra tan exótica! ¿Dónde era? ¿Cómo llegaríamos allí? Resultó que debíamos cruzar el océano Atlántico hasta el puerto de Buenos Aires en Argentina y continuar por tierra desde allí.

Buenos aires era prometedor porque sabíamos que una importante comunidad judía estaba allí desde antes de la guerra; así, ése fue su destino.

Llegamos en un barco el 4 de julio de 1947 llevando documentos falsos que indicaban que éramos católicos, pero recién en 2005 pude descubrir por qué había sido necesaria la falsificación.

Uki Goñi, un investigador que estudió la inmigración de nazis a la Argentina y autor de “La Auténtica Odessa”, publicó una carta abierta exigiendo que la llamada Circular 11 fuera reconocida y abolida. Gracias a su trabajo el gobierno argentino finalmente reconoció, luego de décadas de negarlo, que la Circular 11 emitida el julio de 1938 prohibía a embajadores y cónsules proveer de visas a los “indeseables”, es decir, a los judíos y a los republicanos españoles.

Y Argentina no fue el único país en hacerlo. Casi todos los países latinoamericanos lo habían hecho y los Estados Unidos habían limitado mucho la inmigración judía entonces.

Cuando la Circular 11 fue finalmente reconocida y abolida, 67 años después de su emisión, solicité al gobierno argentino la rectificación de mi registro migratorio para que diga judía en lugar de católica. Lo conseguí y mi caso fue un leading case para todos los que debieron mentir acerca de su identidad para ser admitidos después de la guerra.

La Dictadura

Recuerdo el orgullo de mi mamá cuando fuimos al acto del Movimiento Judío por los Derehcos Humanos. Expresar nuestra oposición a la dictadura, abiertamente, en la calle, como judíos, era más de lo que podíamos imaginar.

Con lágrimas en los ojos y la boca abierta, mamá me tomaba del brazo compartiendo el reclamo por los derechos humanos.

Hasta ese momento habíamos vivido en una especie de burbuja evitando cualquier actividad que pudiera provocar un ataque antisemita o poner nuestras vidas en peligro.

Un ejemplo fue que en castellano nos llamábamos israelitas, no judíos, como si la palabra judío fuera ofensiva. De hecho, fue durante ese acto que por primera vez vi la palabra JUDIO escrita en un enorme cartel, públicamente.

Sin embargo, no teníamos todavía un cuadro completo de lo que estaba pasando. No todos tenían conciencia de las torturas, las detenciones y los desaparecidos, los asesinados cuyos cuerpos nunca fueron recuperados.

El silencio que ya existía se volvió doloroso dolía a medida que la gente comenzaba a darse cuenta de lo que de verdad pasaba.

Recuerdo tenerle miedo a los militares y policías, pero por alguna razón desconocida no hice la conexión directa entre el autoritarismo de la dictadura militar con el nazismo a pesar de lo que habían vivido mis padres en Polonia. Sé de otras familias que habían enviado a sus hijos al exterior porque vieron el paralelo con la Shoá.

Como resultado de haber ingresado al país mediante un engaño y con el recuerdo del antisemitismo polaco todavía fresco en nuestra memoria, durante mis años infantiles mantuvimos nuestra condición judía de manera privada, casi como si no existiera.

No éramos religiosos ni pertenecíamos a organización judía alguna. Nuestra identidad era mantenida solo en canciones y algunas tradiciones.

Pero todo iba a cambiar con la bomba de la AMIA.

1994 La bomba de la AMIA

El 18 de julio de 1994, aquel día inolvidable, mamá me llamó por teléfono. Estaba llorando y me pedía perdón por haberme traído a la Argentina. “No sabía” sollozaba “creí que estaríamos seguros aquí” su llanto se hacía más fuerte, le pregunté “”¿qué pasó mamá?” y su respuesta cambió mi vida: “Bombardearon la AMIA, ¡nos quieren matar otra vez!”.

La mutual judía era un centro muy importante de la comunidad judía argentina. Había estado allí muchas veces en conferencias, conciertos y otras actividades. Era un sitio icónico y en muchos sentidos un refugio.

¿Pero bombardeada? ¿En el centro de Buenos Aires? ¿Y por qué me dijo nos quieren matar otra vez? ¿A nosotros? ¿A mí? ¿Y por qué “otra vez”?

La bomba de la AMIA me volvió judía otra vez. No había elegido serlo antes, simplemente había nacido así. Pero entonces abracé voluntariamente la decisión. No podía huir del hecho que en el “nosotros” de mi mamá estaba incluida yo.

Y el “otra vez” era la Shoá. Aquel “otra vez” me indicó que era hija de sobrevivientes del Holocausto y que eso era también parte de mi identidad.

Esas palabras “nosotros” y “otra vez” fueron las encrucijadas de mi vida. Así, a los cincuenta años, decidí tomar un nuevo camino.

Comencé a buscar a otros hijos de sobrevivientes y los encontré.

Fui a Marcha por la Vida en Polonia donde reencontré el polaco, mi primer idioma, junto con tradiciones y comidas que me eran familiares.

Si el Holocausto no hubiera sucedido Polonia habría sido mi hogar. Habría sido como cualquier mujer polaca que veía caminando por la calle y jamás habría llegado a Buenos Aires.

Fue un sentimiento abrumador.

Recorrer los sitios del Holocausto me conectó fuertemente con lo que estaba empezando a aprender.

Fui a la Fundación Memoria del Holocausto y me sumé más tarde al equipo que registró testimonios para la Fundación creada por Steven Spielberg.

Estos testigos eran los “Niños de la Shoá”, y algunos eran muy poco mayores que yo.

Mis padres habían perdido a su primer hijo, Zenus, un hermano que nunca conocí. Fue entregado a una familia cristiana para que lo salvara mientras mis padres estaban escondidos pero no pudieron recuperarlo. No sabemos si sobrevivió o no.

Podía ver a mi hermano perdido en cada uno de los “niños de la shoá” que habían testimoniado.

Escenarios y horizontes.

Durante los primeros años después de la guerra, la forma en que el Holocausto era mencionado no era como lo que había vivido en mi casa. Los héroes del gueto de Varsovia glorificados. Los horrores enfatizados todo el tiempo. La idea de que los sobrevivientes no podían recuperarse de los traumas vividos.

Nada de esto coincidía con mis experiencias en la infancia ni con muchos sobrevivientes conocidos.

Empezó mi búsqueda en libros que ofrecían nuevas perspectivas y me permitían reconstruir una narrativa diferente sobre la experiencia de los sobrevivientes, una que coincidiera con la mía, que luego intenté difundir lo más ampliamente que pude.

Unos años después, junto con otros sobrevivientes y sus hijos, fundamos Generaciones de la Shoá en Argentina y comenzamos con varios proyectos educativos.

Uno de esos proyectos fue los Cuadernos de la Shoá en donde planteamos, en cada número, temas marginalizados como los rescatadores, la experiencia de las mujeres y los niños, las búsquedas de salvación, la instalación y destrucción de los guetos, los campos de concentración, la progresión de los ataques, las diferentes maneras de supervivencia, los otros genocidios del siglo XX, los programas de exterminio, la deshumanización.

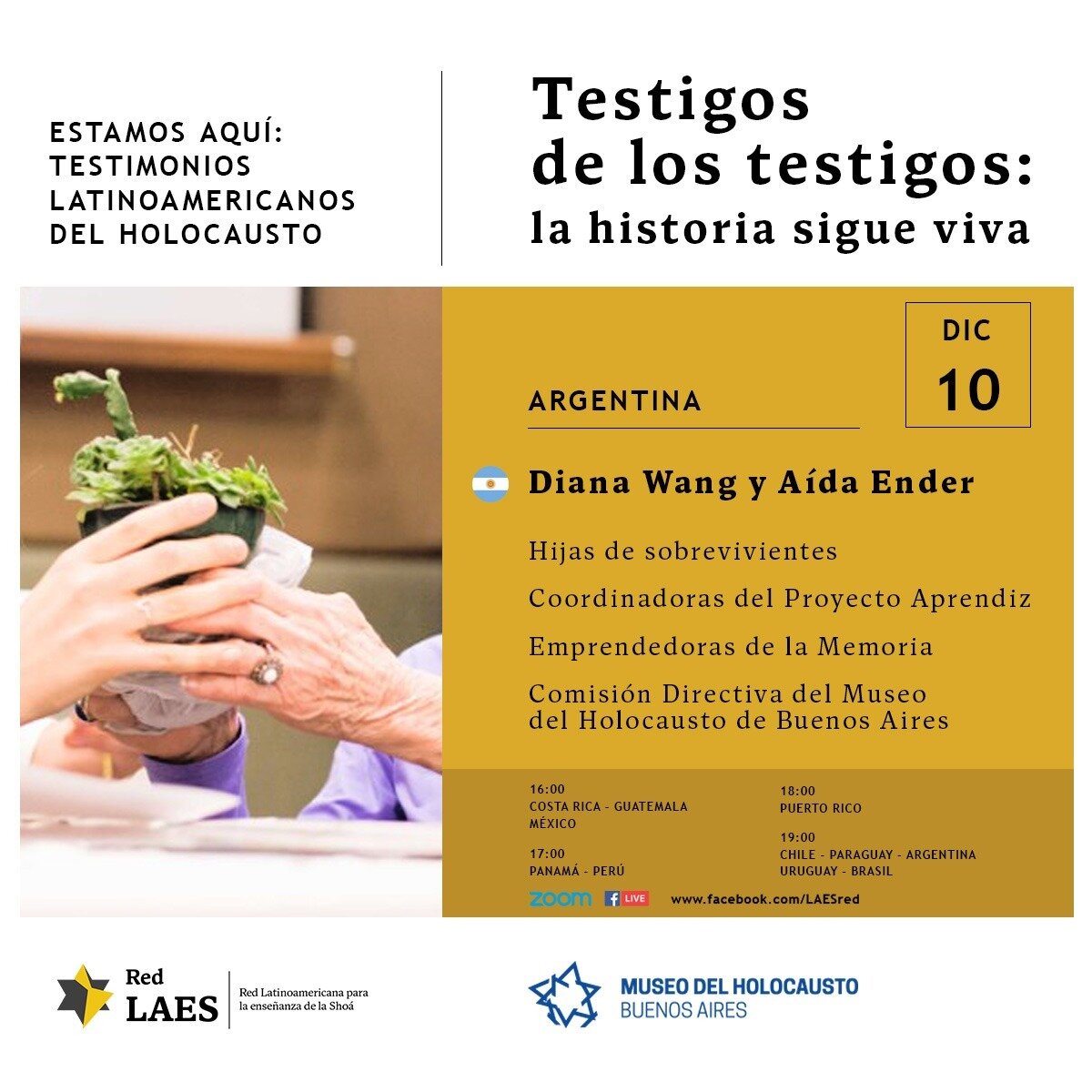

También creamos el Proyecto Aprendiz, un desesperado intento de mantener vivos los testimonios orales de los sobrevivientes para asegurar que una vez que no pudieran ya hablar habría alguien que podría continuar hablando en su lugar.

Y finalmente, en 2018, nos sumamos al Museo del Holocausto de Buenos Aires que creó una exhibición interactiva maravillosa. Desde allí continuamos nuestro trabajo con nuestros proyectos y la intención de crear nuevos.

Outline

Introduction to key themes and tension [Refuge for Nazis like Eichmann; yet home to Holocaust survivors] - from the description of event for whoever is introducing us!

Immigration and National Belonging [Natasha]

This is context for what Natasha calls a “tenuous belonging” in her book

Pre-Holocaust: History of Jewish belonging in Argentina (a “nation of immigrants” that also became home to the Semana Trágica (an urban “pogrom”) → revealing the tensions for Jews who were able to have religious institutions, create vibrant Yiddish press, theatre, etc., yet still grapple with antisemitism and questioning their belonging, often through violent means

Argentina during WWII/first postwar years [Diana leads; then Natasha]

Her experience and her families in immigrating to Argentina (and many others); Diana can speak to silence as well as the laws that put quotas on Jews immigrating to Argentina, forcing them to enter Argentina with falsified/forged documents

Natasha can speak to how this manifested in the experience of her other interview subjects as well

Diana: Argentina During and Shortly After WWII

For those who survived and found themselves still alive, the end of the war wasn’t a time for celebration or joy.

Europe was covered with the blood of their missing families, and they also faced the menace of a Cold War. They knew that they had to find another place to live.

Yet, the sad result of the 1938 Wannsee conference—that no country would accept Jewish German or Austrian refugees—repeated itself at the end of the war. Survivors did not know where they could go.

My parents, who had survived the war in Poland, and who had lost their first child, carried an infant around -me- as they, with many others, looked for a place that would welcome us. The embassies and consulates had long lines with virtually no good news, and it didn’t take them long to realize that their Jewishness was the problem.

So, they decided to say they were Catholics instead, as they were already well-versed in doing whatever it took to survive. That was how, with the help of a bribe, we obtained a visa to Paraguay.

Paraguay? What an exotic word! Where was it? How would we get there? It turned out that we would need to cross the Atlantic Ocean to the port of Buenos Aires in Argentina, and, from there, to continue overland.

Buenos Aires was promising because we knew that a large Jewish community had already been living there in peace since before the war; and so that became our destination.

We arrived on a ship on the 4th of July, 1947 holding false documents that stated we were Catholics, but it wouldn’t be until 2005 that I would eventually discover why those falsifications had been necessary.

Uki Goñi, a researcher studying the immigration of Nazis to Argentina and author of the book The Real Odessa, published an open letter demanding that what was called Directive 11 should be recognized and abolished. Thanks to his work, the Argentine government finally recognized, after decades of denial, that the secret Directive 11, enacted in July of 1938, prohibited ambassadors and consuls from providing visas to “undesirables''—i.e. Jews and Spanish Republicans.

And Argentina was far from the only country that did this. Almost all Latin American countries had done it and the United States had extremely limited Jewish immigration then.

When Directive 11 was finally recognized and abolished, 67 years after its enactment, I asked the Argentine government to rectify my immigration records to state Jewish rather than Catholic. I succeeded, pioneering the case for many other Jews in Argentina who had to lie about their identity in order to be admitted in the years after the war.

Dictatorship years [Natasha leads; then Diana]

speak of the experience of Jews during the 1976-1983 dictatorship and the antisemitism during those years

Also the role of Jews in the human rights movement [including Rabbi Marshall Meyer]

but then, some of the silences and tensions in the community [Diana can speak from the first person about this]

Diana: The Dictatorship

I remember my mother’s pride when we went to the first march for the Jewish Movement for Human Rights. Expressing our opposition to the dictatorship openly, on the street, as Jews, was more than we could have ever imagined.

With tears in our eyes and mouths agape, my mother held my arm while looking upon the crowds willing to fight for human rights.

Until that moment, we had lived in a sort of bubble, avoiding any kind of activity that could provoke an antisemitic attack [or put our lives in danger].

One example was that in Spanish, we would call ourselves - “israelitas” (Israelites) instead of “judíos” (Jews), as if the term “Jewish” was offensive. In fact, it was during that march that I saw the word JEWISH, written on a big sign, publicly for the first time.

However, we still didn’t have a good picture of what was going on. Not everyone was aware of the torture, inprisonments, and the “desaparecidos”, the murdered people whose bodies were never recovered.

The silence that existed continued and became painful to realize as people began to learn what was truly going on.

I remember being afraid of the military and the police, but for some unknown reason I did not make a direct connection between the authoritarianism of the military dictatorship and Nazism, despite what my parents had lived through in Poland. I know of other families who sent their children abroad because they did see parallels to the Shoah.

As a result of having entered the country under false pretenses, and with the memory of Polish antisemitism still fresh in our minds, for much of my early years, we kept our Jewish identity private, almost as if it didn't exist.

We were not religious and did not belong to any Jewish organizations. Our heritage manifested only in songs and a few traditions.

But everything would change with the AMIA bombing.

1994 AMIA Bombing [Diana leads, then, Natasha]

Diana can speak of her experience of the attack, and how it resonated for in relation to her mother as a survivor; what it galvanized for her in terms of her own engagement with Holocaust memory with March of the Living, going back to Poland, and starting her work with the group Niños de la Shoá (Child Survivors of the Shoah) and later Generatiosn of the Shoah and the Holocaust Museum of Buenos Aires

Natasha can provide additional context from her perspective as an ethnographer on the power of testimony and survivors/family members of victims’ voices in the efforts for justice and human rights, also reflecting on working with social movements like Memoria Activa and Diana’s groups and how this fits into context of other human rights/social justice movements; and her concept of “acts of repair” (from her book)

Diana. 1994 AMIA Bombing

On July 18th, 1994, that unforgettable day, my mother called me. She was crying as she asked my forgiveness for having brought me to Argentina. “I didn’t know”, she sobbed, “I thought that we would be safe here”.

As her crying intensified, I asked “What happened, Mom?”. Her response changed my life, “The AMIA was bombed. They want to kill us again.”

AMIA, the Argentine Jewish Mutual Aid Society, was the most important Jewish cultural center in Argentina. I had been there numerous times for conferences, concerts, and other activities. It was an iconic place and a refuge in many ways.

But bombed? In downtown Buenos Aires? Why was she saying they want to kill us again? “Us”? Me? And why “again”?

The AMIA bombing made me a Jew once more. I was born Jewish, and did not make an active choice to be Jewish. But this time around it was a conscious and voluntary decision. I couldn’t run away from the fact that my mother’s “us” included me.

And the “again” was the Shoah. That “again” taught me that I was a child of Holocaust survivors and that that was also a part of my identity.

Those words,“us” and “again”, were turning points in my life. And so, at fifty years old, I decided to forge a new path.

I began searching for other children of Holocaust survivors, and found them.

I went to the March of the Living in Poland, and there reencountered Polish—my first tongue—along with familiar traditions and foods.

If the Holocaust had never happened, this would have been my home. I would have been just another Polish woman like all the others I saw walking on the street and would have never traveled to Buenos Aires.

It was an overwhelming feeling.

Traveling to Holocaust sites afforded me a strong connection to what I was beginning to learn about.

I went to the Fundación Memoria del Holocausto, the Holocaust Museum of Buenos Aires, and joined the team collecting testimonies for Spielberg’s USC Shoah Foundation – The Institute for Visual History and Education (formerly known as Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation).

These witnesses were the “Shoah’s children”, and yet only a few years older than me.

My parents had lost their first son, Zenus, the brother I never met. He was given to a Christian family to look after him while my parents were in hiding, and they were never able to get him back. We don’t know if he survived or not.

However, I could see my lost brother in each one of those “children” who had given testimony.

Diana can speak about the current landscape of Holocaust education and awareness from the museum’s perspective; their new work with Holocaust memory with the program “Proyecto Aprendiz” (Apprentice Project)

Natasha can speak about the landscape of justice - including new trials for dictatorship-era crimes along with ongoing impunity in AMIA case; also additional dilemmas related to reframing of dictatorship as a genocide and the nuances of the legacies of the concept of “Nunca Más” (never again) in relation to the dictatorship and Holocaust

Diana. Landscapes and Horizons

During the first years after the war, the way in which the Holocaust was typically discussed was not as I heard it at home. The “heroes of the Warsaw ghetto” would be glorified. The horrors would be highlighted over and over again. The assumption was that the survivors had been left with hopeless trauma.

None of this matched, however, with what I had experienced in my childhood nor with the many survivors I knew.

So I sought out books from authors who offered new perspectives and began to reconstruct a different narrative of the survivors’ experience; a narrative that matched my own, which I then tried to spread as far and as wide as I could.

A few years later, together with several survivors and their children, we founded Generations of the Shoah in Argentina and started a handful of educational projects.

In one of those projects, Cuadernos de la Shoá, the Shoah Notebooks, we discuss in a number of volumes such marginalized topics as: the rescuers, women’s experiences, children’s experiences, their endeavor to find a safe haven, their forced removal to ghettos and concentration camps, progressions of antisemitic attacks, different ways in which they survived, other genocides of the 20th century, and other engineered programs of dehumanization.

We also created the Apprentice Project in a desperate attempt to keep the oral history of survivors alive; wanting to ensure that once they were no longer able to speak, there would be someone else who could continue to speak on their behalf.

And finally, in 2018, we joined the Holocaust Museum of Buenos Aires, which created wonderful interactive exhibits and from where we continue to work on our projects and aiming to create new ones.